Sunday, August 24, 2008

Vicky Cristina Barcelona

Rebecca Hall is channeling Mia Farrow here, as the mousy, neurotic woman who is suspiciously good at "getting what she wants" (that's my reading, following Hannah and Her Sisters and Husbands and Wives). She is just sexy enough to be believable, and her nervousness is easily its own equivalent of the volatile energy of Cruz.

What I like about this movie: it takes an interesting situation, and slowly unfolds it through several developments and a small twist. One could compare it to Bergman's last film, Sarabande, in the way that a few characters are walked-through complications in their desires, without any big action or false resolutions. Husbands and Wives would be an excellent reference within Allen's ouevre.

Whether one likes this film or not probably depends on your tolerance for the voice-over narration. To my ears, it was pure Flaubert: ambiguous, falsely even-handed, arrogant, but completely banal. Anyone who tells you the narration was "obtrusive" is just telling you they haven't read Madame Bovary.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

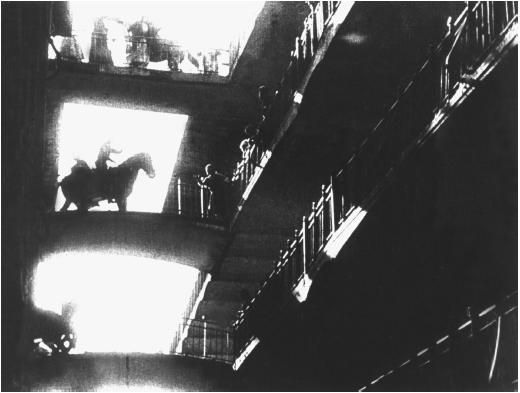

The Human Condition (1959)

My point is simple and almost a truism: the bigger an artistic work is, the more it has to offer "big" truths. This is why an excellent TV show like The Wire (a 1-hr program) is fundamentally lacking the depth of a merely "good" 2 hr film. It is not a matter of entertaining us for a set length of time. It is a matter of ambition and statement. Believe me, 2 hours of the Wire packaged together as a feature-length film would be sorely disappointing.

I feel silly dwelling on this aspect of common sense, but I suspect it is a bit elusive in its logical result: the best movies will be (those which "pull off" being) the longest, the best books will be the biggest, the greatest operas will be the most uncomfortable to sit through, etc. The "finely made" little thing has to be *that much* more finely made to compare. Thus, epic poetry > lyric.

Put in those stark terms, few are likely to agree with this "common sense" any more. Indeed, many are apt to get defensive. But again, these truisms have their logic: War and Peace, Paradise Lost, Wagner, Proust--are these not the great achievements of their respective forms?

Probably the finest made "little" film is The Rules of the Game. It says a lot about French society, but by way of types and microcosm. A movie like The Human Condition tries to say a lot by showing the "whole thing" itself. And the amount shown here is astonishingly vast. Nonetheless, the insight (which The Rules of the Game or The Leopard excel in) is a bit flat here.

This is all a bit abstract. Frankly, the movie is too long to review as a movie. It consists of the destruction of a conscientious and moral man by the combined brutality of selfish or cowardly individuals and society's merciless exploitation of other humans. It would be simple to say that the movie's hesitations about Marxism are its blind-spot, but in 1959 a Marxist film would have been so "Soviet" as to be worthless in another direction (i.e.-the great Soviet films are much earlier). In short, the panoramic viewpoint of the film contains a jarring number of false notes, which are but poorly reconciled.

Morally, however, the film is supreme. I was frequently moved to tears. Technically, it is a great accomplishment, and the direction and Nakadai's acting are phenomenal. Almost the *only* thing lacking is some unifying penetration into the real state of things, the human condition, which would justify the length of the the film and reconcile its individual portraits.

One's ten hours are "well spent" watching this film. But the whole is less than the sum of its parts, and it does not compare favorably with Berlin Alexanderplatz or War & Peace. Perhaps this is why I have heard of those novels, and not the novel on which this film is based.

Friday, July 25, 2008

The Dark Knight

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

Wall*E

The plot is not so very different from the General, but the movie goes wrong wrong wrong by trying to stir up our sympathy for humans. That is, it's as though in the General, our sympathy had to be on both sides of the Civil War at once. We like Wall*E, and we our engaged in his pursuit of love, but the movie hits a series of false notes when we are asked to side with the humans (fat, stupid) over the robots (full of personality, quirky, sensitive).

This is a story of redemption; *our* redemption, by the actions of those who understand and love us better than we love or know ourselves. Wall*E is a FAN of humanity, where we have become alienated from it. So far, so good. But the mistake is the "evil computer" plot imported here from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In other words, the ACTION does not take up the central conflict or theme (redemption) at all. For an example of action that does take up the central conflict of a work, we need look no farther than 2001: the theme of evolution and the fate of humanity's development is played out IN THE PLOT, viz., will the computer be the "next step" in mental life, or the giant space baby? This is an existential question, but also the question of the success or failure of the mission. Wall*E is all over the map in thematic/sympathetic terms, and so all the action involving humans is more central than it ought to have been.

That is my only real complaint, but it's a big one. In frank terms: the plot should have been something else.

Saturday, June 28, 2008

Goyokin (1969)

1) the genre needs to be taken in a strict sense; viz., action films where the plot turns on sword-fighting

2) thus, not Rashomon, but certainly The Hidden Fortress.

3) I'm in no position to draw a timeline here, but the early films we have to associate with the genre tend to star Toshiro Mifune (Seven Samurai, the Samurai Trilogy, Throne of Blood, The Hidden Fortress, Chushingura, Yojimbo, Sanjuro).

4) so, what *looks like* a "classic" period would be 1954-1962

5) afterwards, one has the highly critical samurai films: Samurai Rebellion, Harakiri, etc. in which loyalty and the samurai code are shown as deeply flawed.

6) By the end of the 1960s, this genre appears to have died out, and the notable 1970s Samurai films are the trashy and mega-violent Lone Wolf and Cub films (which are wonderful but have nothing to do with the earlier era).

Goyokin is truly a film at the end of its genre's possibilities. Big, expensive-looking, shot in color, and overlong, the film is truly "decadent" in every sense. The plot is VERY straight-forward, the character development is... not there, and the end is *about* the genre's inability-to-continue (historically, the point where samurais face their demise). In this sense, it is analogous to the later John Wayne films (The Shootist) or the Wild Bunch.

There are some beautiful shots, and the final battle is a real highlight, topped only by the weird refusal-to-end that takes up the last 10 minutes. But there are no interesting situations to remember, and the movie's strategy is akin to that of Napoleon's 1813 battles: bulk relying on what has worked before, but lazily and to little effect.

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Get Smart

Get Smart doesn't need a lot of reviewing, so I'll just lay out the basics:

Unlike most comedies of this sort, the good jokes don't start to fall until the middle third of the movie. This is strange, because the first third is the stuff of the TV series, which should be reliably funny. Instead, the movie finds humor where it can get it, which happens to be in an extended and pointless James Bond-like crashing-an-eastern-european's-swanky-party-while-searching-his-house-for-secret-plans scene. Those are always the best part of the Bond movies, so it works here for Get Smart's first laughs. The first half-hour is weirdly unfunny, given that it is basically office politics, something Carrell is superb at.

The final third of the movie, though, is simply unrewarding. Do I care if the President (James Caan) blows up? No. Am I surprised at the identity of the double agent or in Max's and 99's budding relationship? No. And yet all these explosions and near-death escapes are thrown at me as though I do. It's all very tiresome. The naive thing to say would be, "It just turns into a regular action movie." But I LIKE regular action movies, y'know?

Carrell, Alan Arkin, and Terence Stamp are all fantastic here, while Anne Hathaway ought to have filed an injunction against the film being released. She is wooden. It is hard for me to believe this will not single-handedly destroy her career. The Rock, as usual, wears thin after about 4 minutes.

Most of all, the movie seems rushed and incoherent. In the opening credits, we see that Max's life is a mess: his milk is curdled, his goldfish is dead, etc. But, wait--in fact, he seems to be the most organized, driven, and reliable person in the fucking world. It seems the movie doesn't understand its own protagonist.

Get Smart comes out of the box already-dated and out of touch. But not, as one might expect, because its 1960s TV reference no longer sticks---rather, because it seems so very late 1990s. You know, when Mike Meyers was making those other movies.

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

R.I.P. Sidney Pollack

What is much more important for me is that Sidney Pollack was one of THE great character actors. Who doesn't recall the turn-off-your-cell-phones clip that played before movies last year? ("We don't interrupt your phone calls--don't interrupt our movies"; with Pollack "directing" someone's break-up phone call)--it was a dumb idea, but one thing was very clear: Sidney Pollack plays a terrifying, self-assured asshole like no one else.

A lot of this was Pollack's voice and physical presence: everything Burt Lancaster was going for in The Sweet Smell of Success, but without the gay (under?)tones. While usually bespectacled and obviously "civilized," Pollack could switch into "threatening" with utter believability.

I even remember his character's name in Michael Clayton, an utterly forgettable film: Marty Bach! Of course! Who else could have played Marty Bach?

The same is true of his character in Eyes Wide Shut---well, really it's the same character. Your older friend, whom you trusted, who fucked you over, and is now expecting you to hold his shit.

Pollack is really truly great in the 1992 Woody Allen movie Husbands and Wives, especially one scene where it is entirely possible that he is going to murder Liam Neeson. The entire movie would fall apart if anyone else had had to play this role. One instantly recalls a scene where Pollack drags his new girlfriend across a driveway to his car. "He could kill her," you are thinking every second of the way. It's something Woody Allen's films normally stumble over, but Pollack was a genius casting decision (in his first starring role) that makes the whole movie work.

So, not an extensive filmography, and not an illustrious one. But like a great fielder on an otherwise mediocre baseball team, Pollack's acting raised the level of everything he was part of. Will we remember Out of Africa? Probably not. But Pollack's acting in the films of *other* directors (Kubrick, Allen) will always be worth another viewing. Mr. Pollack, we will miss you.

Friday, May 23, 2008

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008)

Oh but wait, the man who brought us The Phantom Menace wrote the story? And a 66-year-old man will star? Now we're cooking.

But let me come at this another way. At some point in the movie, 5 or so people are in a boat on the Amazon, which is about to hurtle over several towering waterfalls. "Oh no!"--you are supposed to think. But I thought, "Who *are* these people?" It's hard in this movie to 1) remember if a character was in the earlier films (Karen Allen) 2) is a new, annoying addition meant to seem like he is from the universe of the earlier films (Ray Winstone, John Hurt, Jim Broadbent [the dean]) or 3) an entirely new character meant to draw in specific audiences (Shia LaBeouf and Cate Blanchett). So, when I should be worrying about whether they are going to survive this waterfall-jump (ripped off from the Fugitive, let's be honest), instead I am thinking--"maybe these characters are from the Temple of Doom movie," which I've not seen.

So the film has what wikipedia would call "Extended Universe" issues. The largest of these is the plot device itself, which was made into a theme-park ride during the decade of development on the script. The crystal skull is bound to annoy and disappoint everyone. The theater audience I saw this movie with were a real bunch of dolts, but I think a more sophisticated crowd might find certain skull-related scenes risible.

Basically, if you know what the word "risible" means, you might have a chance to use it describing this film.

Are there people-eating ants? Yes. Is Shia LaBeouf less annoying than we suspsected? Yes. Have we not always wanted to drive a motorcycle through an Ivy League library? Yes.

On the other hand, Cate Blanchett's much-touted role might have been played just as well by virtually anyone, the movie is about 15 (specific) minutes too long, some scenes are a bit "Sky Captain"-ish, and it ends badly.

The main question you are asking is, does it COUNT as an Indiana Jones movie? Or is it like the Velvet Underground album without Lou Reed? The crappy part is, yeah, it counts. It looks (about) right, that famous score is there, Harrison Ford is good, people with accents continue to be evil, and you kind of get into a lot of the scenes. But that's about all. To put it in my terms, you stop hating on Harrison Ford's pants as a 2008-abomination about 40 minutes in, and from that point on, the movie is Spielberg's to lose.

Saturday, May 17, 2008

Star Wars (1977)

But what about when the startlingly weird has become so familiar that we approach it with utter familiarity, unflinchingly?

This is the case with the Star Wars films. The first film has two oddities in its title, "Episode IV" and the subtitle "A New Hope." When the film opens, and the scrolling introduction shows that we are already on the fourth episode--well, if anyone ever asks for a good example of what I take pretentiousness to be, it is this "Episode IV" business. And isn't the film just called "Star Wars"? Not until The Phantom Menace ruined the convenience of saying, "the first one," did it become necessary to ever *say* "A New Hope."

The confusing introduction is succeeded by ~20 minutes of one robot talking to himself--in space, in the desert--before we meet our hero, the ridiculously-named and badly-acted Luke Skywalker. At this point, the film settles into a fairy tale/adventure plot that is easy to follow: his family is murdered, he runs off to join the rebellion and take revenge, meets strange and exciting new people, is captured, escapes, loses his mentor, but wins the day in the big battle. A lot of ground is covered very quickly and not always coherently. Nonetheless, once Alec Guinness shows up, the movie is in good hands, and Harrison Ford brings some much-needed coolness to the nerdiness of the first half.

Compare this film with the near-contemporaneous Alien. While Star Wars is not "really" a sci-fi movie, but is obviously in the Arthurian tradition (what else could explain the light sabers?), Alien is also not really a sci-fi movie, but is truly a horror movie. Both movies have long, slow build-ups that I can imagine would tax most viewers' patience nowadays, but Star Wars chooses to spend this time with a lot of awkward explanatory dialogue, while Alien just sets mood. In Alien, the viewer initially does not know that there *are* aliens (title notwithstanding)--we are terrified when they pop up, just as the crew is. In Star Wars, ever oddity is weirdly taken for granted: nothing in this universe is weird FOR the characters.

The lesson here is, viewed "as though for the first time," Star Wars is clunky and weird. The Empire Strikes Back is the superior movie because it dispenses with much of the exposition and just advances several plot lines simultaneously (like Die Walküre as compared to Das Rheingold). On the other hand, Star Wars is made to be watched over and over--it is a film for nerds who want to know everything about this imaginary universe. There is no need for mood or even coherence. Alien is a well-made film. But I will never want to "go deeper" into its world.

The logic seems to be that something happens in the film because "that's what happens next in Star Wars." This is maddening from a technical perspective, but it is ideally made for fans (The Good the Bad and the Ugly is like this, too). Star Wars has surprisingly little action, only a dozen or so speaking parts, and truly awful dialogue. Long stretches are without charm. But like the Bible, King Arthur, the Song of Roland, or anything else you know the story of by heart, every part of the movie turns out to be perfectly situated and masterfully-ordered. Not because it couldn't have been done better or tighter, but because for all the weirdness of the organization, I want the same thing that is in my memory up on screen again: that's "how it goes."

Wednesday, April 16, 2008

Shine a Light

The Rolling Stones could play every song off their first twelve albums and early singles--probably 8 hours of music--as well as their scattered hits from the 70s and 80s, and have filled over four such documentaries with nary a bad song. Instead, they take the innovative path of playing numerous unfamiliar and unpleasant songs from little-known records such as Undercover. There are three songs off Some Girls, three off Exile on Main St., two off Let it Bleed, and one each off of Beggar's Banquet and Sticky Fingers. This is a strange image of the band's legacy: no "Ruby Tuesday," "Under My Thumb," "Paint it Black," "Gimme Shelter," or "Street Fighting Man"? Or more to the point, none of the mega-hits "Beast of Burden," "I Know It's Only Rock and Roll," or "Miss You"? That is to say, I found the set list unbearably pretentious and miscalculated. The only explanation I can find is, it would be impossible to play every hit--so why try? The solution that Bob Dylan has found--to constantly reinvent his most popular songs in new styles--does not suit the Stones, who have been playing in the Exile on Main St. bombastic made-for-the-Super-Bowl-halftime-show style for over 30 years.

As a movie, it ain't much. The IMAX theater I saw it in made it almost unbearably huge and hard-to-follow. The cuts are dizzying, and the sound is shapeless. Because Ron Wood and Keith Richards barely play the guitar riffs, most of the band's sound is anchored, not by (as one might assume) some invisible third guitar player, but by the ringer bass player and an omnipresent keyboardist. The result is chaos: constant soloing and songs stretched out usually for an extra minute of pure enthusiasm. The much-needed interludes of interviews and "flashbacks" help with pacing a great deal, but one has all the more respect for these elderly men when you realize how tired one gets just *watching* them.

The most interesting thing to say about this film is, I believe: why did this group of musicians commit to this path so long ago and not deviate from it? There is something so utterly tasteless about the arena-rock of post-1960s Stones, that has somehow become the ultimate formula for the world's most successful rock band. The key, I think, is in the presence of Hillary and Bill Clinton in the film: the Stones are the ultimate in bloated comfort, like Bill Clinton's oratory, and in an impossible-to-locate efficiency, like Hillary's nebulous fashion. Bill Clinton is a famously popular and rousing speaker--and yet his speeches are utterly forgettable and notoriously long. That barely any guitar RIFFS can be heard by this band that virtually invented the guitar riff, is paramount. And oddest of all is that none of the dozen performers onstage finds this odd, that everyone in the audience appears to be having the time of their life-- that is, that this problem (the shapelessness of the music) is not felt by anyone else as such. And since the Rolling Stones as well as invented the kind of rock music we have today, why did it end up *here* of all imaginable scenarios?

Saturday, April 12, 2008

Polish Film Posters

Friday, April 11, 2008

Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Not every movie can age well. Midnight Cowboy has not aged well.

What does this mean? You might think I am saying that there may have been some quality in Midnight Cowboy which was originally present, but which has not survived down to the present day.

What I actually mean is that Midnight Cowboy is a bad film. The only aesthetic criteria I can possibly have are my own, i.e. those articulated and determined by (or against) the contemporary background. A film which has "aged well" is an old film that is good. This can be the only possible meaning of these words. We would never say of an out-of-print, unreadable 18th-C epistolary novel that is has "not aged well, *but*...." There is simply no "but"--a film that has aged well is a film that appears good to our standards. What has changed, of course, is not the film itself, but these standards. What we mean to say, then, is not that the film has aged well or poorly, but that we do or do not regard a film as being good (against a background of our previous ratings of said film).

I for one cannot imagine a more interesting question than why and in what ways these criteria change. But that is for another blog. I should just say here that what you remember about Midnight Cowboy--the great acting, the handful of quotable scenes, Jon Voight's endearing stupidity, how gross and intimidating New York can be--that stuff is all there, and it's all enjoyable. What you don't recall--the plot--is simply absent.

You may also have forgotten the cryptic and intrusive psychological flashbacks that attempt to give a "key" to understanding Voight's psyche, but without any payoff or weight. Or how the soundtrack plays the same song into the ground for the whole running time. Or how little significance (socio-historical, moral, plotwise) Rizzo's death has aside from conveniently getting Joe out of NYC.

What we learn about 1969 from this film will likely be analogous to what future generations will learn about *us* when they re-watch Crash in thirty-five years. For a "boundary-pushing" sixties film with a famous soundtrack and starring Dustin Hoffman, you would do better to watch the also-overrated The Graduate.

Monday, March 31, 2008

Real Life (1979)

This film, written by, directed by, and starring Albert Brooks, has one major problem: Albert Brooks is not funny. I wince every time he is on screen. His presence in the plot (a parody of PBS' "This American Life") is unexplained. His voice is grating. I don't understand his hair or bone-structure. The 1970s seem awful.

Charles Grodin (Beethoven's 2nd) is the best part of the film, along with a hilarious running gag about the unobtrusive, Dutch headgear-cameras the crew use to film Grodin's family. But every time Albert Brooks comes on, the film comes into orbit around what I imagine was thought to be a winning personality in the 1970s. What is thought to be the film's selling point, then, is really its biggest weakness: without Brooks, this movie might actually be good. It would also be about 15 minutes long.

To elaborate: most comedies that are turned off the assembly line tend to be "carried" by a personality, such as Will Ferrell, Adam Sandler, Jim Carrey, etc. The movies of each actor are interchangeable with all of his others (Blades of Glory for Semi-Pro; The Mask for Ace Ventura; Billy Madison for Happy Gilmore). Nonetheless, it is true that these movies *are* carried by these actors. No one wishes there were more Courtney Cox in Ace Ventura. Albert Brooks, on the other hand, has pretensions here to be something of an auteur, but also brings a total anti-charisma that jeopardizes all his good ideas. I now know what it must be like to watch Woody Allen movies if someone detests the whiny, ubiquitous Allen character.

The Anthology Film Archives screened this and another early Brooks film (Modern Romance) with the caveat that Brooks is "no Tati," but that he did a couple of interesting things with editing and humor that were worth watching. I admire the modesty of these aims. But, for all that, Real Life is a bad movie that has very little even to say about the topic (reality television) that it has the unique opportunity to be prescient about. And in defense of Albert Brooks as an actor, might I refer you to his excellent performance as an unlikable liberal jerk in Taxi Driver.

Eyes Without a Face (1960)

Like nearly all cult films, which in recollection seem brief, memorable and action-packed, the film is (in the watching) unbearably talky. End of point.

As Mr. Strick pointed out at the screening, the film is very Cocteau-influenced. To this I would add, Hitchcock's family dynamics, something of the Gothic, and a score that prefigures Danny Elfman's work for Tim Burton. This all overstates the film's style a bit, since the sets are cheap and a great deal of the scenes unremarkable, but when these elements come to the front, one immediately starts to attention.

Neither a great movie nor essential viewing, I can't help but feel that I will watch this movie again in my life and enjoy it again, as well. It has a weird, squirmy uniqueness that is all the more enjoyable as it lapses in and out of self-awareness about its B-quality, its camp, and its artistic pretensions. Most art-films are secretly B-movies (see: Godard), but this B-horror flick is nearly unique in quietly being something of an art-film.

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Duchess of Langeais

The film is very long. It moves slowly and follows a very Stendhalian logic of advance and retreat, from the first scene to the last. Balzac's easily-imitable style has the last word, of course, but the movie is primarily an exercise in frustration, interior scenes, and uncomfortable dialogue where the game is to say the unpleasant thing that has to be said, without being so clumsy that one can be held account for one's real motives (though they are known).

Jeanne Balibar is a strange beauty, and yet so French that I just had to take it on faith that "this must be what it's like over there," while Guillaume Depardieu is a lumbering, almost canine hunk--he could almost be in the Pirates of the Caribbean, except his sullen, sullen, sullen attitude is completely without charm. He is dull and very passionate all at once; it is a great performance.

I can't recommend this movie for entertainment. The audience I saw it with seemed to miss the point, and I got a bit anxious about whether it would ever end. But, if you like movies, this one is extremely well-made, somewhat memorable, and obviously the work of a master, though this is no masterpiece.

Monday, March 24, 2008

Upcoming Reviews

Bonnie and Clyde

Battleship Potemkin

It Always Rains on Saturday

Eyes Without a Face

and others

stay tuned...

Sunday, March 16, 2008

Ivan the Terrible (1942, 1946)

It is evident in 2008 that Sergei Eisenstein is probably the greatest director who ever lived. Every one of his six films is an unqualified masterpiece. Of the silent directors who made the transition to sound, the stand-outs are obviously:

F. Lang: Metropolis--> M

C.T. Dreyer: Joan of Arc--> Day of Wrath

C. Chaplin: Gold Rush--> The Great Dictator (one could say Chaplin's problems with sound were more as an actor than as a director)

C.B. DeMille: The Ten Commandments--> The Ten Commandments

Y. Ozu: Story of Floating Weeds--> Tokyo Story

J. von Sternberg: Docks of New York--> Blue Angel

In both silent film and sound film, Eisenstein is a titan, but taken together, it can be said that no one made the transition as well as he. No one would compare the sound Testament of Dr. Mabuse with the silent Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (and this is leaving aside Lang's dismal Hollywood work); DeMille's sound epics are ripe for parody; and Dreyer, Ozu, and Sternberg--their important silent films are rather late (Joan of Arc: 1928, Floating Weeds: 1934, Docks of New York: 1928), where Strike and Battleship Potemkin are rather earlier: 1925.

[It really is a shame that sound came along and ruined everything. 1927 brought us Napoleon, The General, The Lodger (Hitchcock!), Metropolis, and Sunrise... and, alas, The Jazz Singer. I don't lament the appearance of sound, but I do mourn the end of silent film as a creative medium.]

Anyways, Eisenstein's work in Ivan the Terrible cements his claim to being the best director of sound films, as well. The pacing, the lighting, the music, the makeup, the battle scenes, the costumes, the bizarre color scene in an otherwise B&W movie!! (I cannot say the script, for I watched it today without subtitles...don't ask.) Countless classic moments, and all in a completely new style from his silent movies.

Now, the naive viewer would be correct in saying that Ivan the Terrible hardly *looks* like a movie from the 1940s. It's hard to believe that this film came after Casablanca, Citizen Kane, Gone With the Wind, etc. There is nothing breezy or ironical about Ivan the Terrible. It is very nearly a tonal monolith, like many great silent films. The point to make, though, is that Eisenstein's silent movies are nothing of this sort. Strike, October, and Potemkin have no characters at all--they are all expressions of collective, anonymous, and spontaneous action. Eisenstein's silent films bear no resemble to the Lang films that Ivan the Terrible somewhat resembles (Siegfried, Brunhilde's Revenge): 1920s Eisenstein would never focus on a Wagnerian king-hero. Thus, October (let's say) is far more breezy and associative than the very Shakespearean Ivan.

This difference is entirely political: Soviet art entered a major retrogression while Eisenstein was trying to make a film in Mexico (never finished), and so historical realism and major world-historical figures took the forefront in Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible, where his earlier films are experimental and always foreground a mass of people, playing down the role of party leadership.

This film is so full of remarkable moments that I can barely run through a list of them all. But the coronation, the siege of Kazan, the chess-board w/ giant shadows, the singing Muscovites in a long line strung out across the steppes, the church-play of the fiery furnace, the assassination in the church, or the jaw-dropping dance scene (in color!)----never a dull moment. One image stood out for me, this viewing, however: Ivan has just realized that his wife has been poisoned (back in Part 1), and he reaches his hands in despair across a table with the poisoned cup on it. And....he has...the most beautiful fingernails you have ever seen. It is stunning. The film is never crude, and the budget seems to have been reasonable, but only at this point does it strike one as a great sound film. We all know that once actor's voices could be heard, it changed the nature of the close-up. A close-up no longer suggests volume. But I don't know that a silent film would ever meaninglessly zoom-in on a pair of beautifully manicured male hands. And really, one might say, this is what is missing from Shakespeare.

Saturday, March 15, 2008

Why we shouldn't listen to artists talk about their work--Funny Games

From A.O. Scott:

His is an especially pure and perverse kind of cinematic sadism, the kind that seeks to stop us from taking pleasure in our own masochism. We will endure the pain he inflicts for our own good, and feel bad about it in the bargain.

[Haneke's] ideas are often facile encapsulations of chic conventional wisdom.

[You, the viewer, are meant to] congratulate yourself for having purchased a dose of Mr. Haneke’s contempt

My favorite blurb comes from the NY Post:

Basically torture porn every bit as manipulative and reprehensible as Hostel, even if it's tricked out with intellectual pretension.

Now, Michael Haneke strikes me as the sort of asshole who would welcome bad reviews. "That's exactly the effect I was looking for!"-- and would delight in bad reviews from America, and would take a bubble bath in bad reviews from the NY Post. But, as one gets older, one gets tired of assholes of this particular species. But A.O. Scott has Haneke right on the money: he's not that smart. Nothing could be further from the truth than the NY Post, which could have been written as a parody of how to misunderstand this film. But equally off-mark is Haneke himself, with his spoutings about the viewer's "complicity" in the violence. This, of course, from someone who makes a shot by shot remake of his OWN movie...

The problem: this film is not WORTH misunderstanding or "intellectually" defending. A.O. Scott is right to conclude that Haneke has better movies than this, but I have to stick up for Funny Games on a movie-going level. We should bracket as inane the ethical questions of "desensitization to violence" that reviewers have focused on, and which Haneke childishly has participated in.

Evidently the new prequel to the Silence of the Lambs committed the ultimate blunder of explaining Hannibal Lector's evil, through some childhood trauma, Nazis, etc. Funny Games, though a remake of a 10-year-old film, is still ahead of the curve in this respect. Everyone will have remarked on this. What should also be noted, though, is that the bourgeois family is equally unpsychologized. A film like The Ref (yes, the Dennis Leary film) knows that, dramatically, an intruder into the family environment naturally brings out the divisions (Oedipal or otherwise) hidden under the placid surface. C.f. also Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and, evidently, the Japanese film Visitor Q.

Funny Games shows no interest in family dynamics. I hypothesize that Haneke threw away this immense dramatic possibility (characters turning against one another, relishing the punishment of their spouse, using the child against the other parent, etc) for a reason. He completely leaves aside the question of whether these people "deserve" their fate, and really is not that interested in how they (psychologically) "respond" to their situation. If Haneke's film earns the boring and cliched descriptor "clinical," it is unclear what kind of clinic it would be--i.e., what is the subject of our observation?

If the film were *truly* a test wherein the audience were "dared" to find sadism interesting, my response would be, it's a rigged game. The only funny and charming characters are the torturers. And without them, there would quite literally be no movie. The film is insufferably boring (read: brilliantly directed) when they are off-screen. To desire more torture is our only hope for a rescue from the non-dynamics of the Watt-Roth dialogue.

Oops, I said I wasn't going to intellectualize this. So, yes, on a movie-going level, the film delivers. It is well-known (from Paradise Lost) that we prefer "bad" characters to good, and Funny Games gives us great and inventive entertainment along these lines. Generically, it is interesting: is it a black comedy? And overall, fewer people die in this film than in The Ladykillers, and none of the violence is onscreen, so I don't see what the fuss is about. A smart movie? In a limited way, and as regards its limits, yes. "Torture porn?" Certainly not. Worth seeing for some great direction, snappy dialogue, and good acting? Well, that answers itself.

Monday, March 10, 2008

Strike (1925)

Anthology Film Archives' "Essential Cinema" series is one of the more off-putting, elitist endeavors imaginable: "Let's screen already obscure, unlikable, and forgotten films... but in a way that renders them unintelligible!" The Dreyer screenings of last week have now given way to Eisenstein's masterworks, and nary a subtitle in sight. For this I applaud them. I may not have the eye for technical aspects (a good or bad transfer, 35 mm vs 70 mm, etc.), but without real film, untampered with and played "straight," as it were, one never *could* begin to distinguish these things. And although I have no interest in making films, I regard every Essential Cinema screening of a classic silent film as of the utmost importance in my education in filmmaking.

It is trivial to discuss the place of Strike within the canon; we may consider it sufficient to mention that Battleship Potemkin and Ivan the Terrible have both placed in the Sight and Sound polls, while Strike and October have not. For myself, I find the three silent films virtually interchangeable in (ludicrously high) quality. Ivan the Terrible may just be the best film ever made. But let me make a little case for Strike as a film you cannot go another day without seeing.

There are no characters to speak of. The plot is one-dimensional. The "meaning" is transparent and blunt. These are qualities of film that we have learned to ask for. Strike dashes these assumptions. Characters are shown to be unnecessary, and perhaps even a juvenile addiction of viewers. Complexity of plot appears weak and trivial. Subtlety seems like mediocrity, a compensation for poor sets and uninteresting shots. This was a direction film did not take. We have long thought of film as a novelistic or narrative genre; failing that, a dramatic one. Strike is symphonic. It *builds*. Motifs are repeated and varied. Individual voices are unimportant. Interludes are purely for tonal effect. And so on.

Like L'Atalante and La Belle et la Bete, I wish I had seen Strike dozens of times as a child. Far from the dour Marxist propaganda one might imagine it to be, one has rarely seen such fun had in filmmaking. One feels very far away from the formalism of Abel Gance's Napoleon, or the realism of Alexander Nevsky. Those are boring films that are "good for us" to watch. Strike, one of the more didactic films ever made, is anything but the chore that implies. And like the greatest films, one begins to forget, while watching it, that reality itself does not look like this. As morons correctly note, in a foreign film, you stop noticing the subtitles after ~ five minutes. In the best moments of Strike, I have never felt as more of a question about *reality*, nudging my friend, "Who are these guys?... Ah. Up to no good, it seems."

Friday, March 7, 2008

The Thin Man (1934)

Mr. Strick's next review will be of A Brief Encounter, a humorless and draining depiction of marriage as "the longest journey" (Shelley)-- in utter contrast to the delightful and frivolous marriage which stands at the center of The Thin Man. The Wikipedia entry for the film series (six in all) describes the couple, Nick and Nora, as "a hard-drinking and flirtatious married couple who banter wittily as they solve crimes with ease." Yes! That is all true.

Although, boiled down to plot elements, the film contains murder, blackmail, bigamy, embezzling, and the like, the main characters are so unfazed by everything that one begins to feel it would be very naive to even care about the crime committed, whose solution is the ostensible motor power of the plot. Let me illustrate this point: in a mystery film, such as Murder on the Orient Express, every effort is made to play up the contrast between the apparent nonsense of Poirot's method, and the stunning results he produces. In the Thin Man, the mystery itself turns out indeed not to have been attended to any more by the screenwriters than by ourselves. All the pleasure, as it were, is to be had along the way.

Dashiell Hammett has earned a reputation somewhere below James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler for American noir novelists, and this is as it should be. The Thin Man skates over the thinnest premise entirely on charm: nearly every minor character over-stays their welcome, explanations and motives are rarely coherent, and the conclusion is absurd and unsatisfying. But we all know what charm is, no? And not only do Nick and Nora Charles (and their dog Astor) have it, but they are married. Married. I can not think of another film that makes being married look this great. Love stories all either lead up to a wedding, with married life never shown, or they deal in adultery. A good marriage is, for most purposes, not a cause of narrative.

This, of course, is true for our happy couple here. They never quarrel, but rather flirt. Nick is retired and they have no money concerns. Left to their own devices, their parties would *not* be invaded by reporters and suspects. The real genius of putting a delightful married couple at the center of a tumultuous murder investigation is precisely how little their marriage "needs" something like this to hold it together. One reason that I imagine the sequels are probably quite good is that there would be no reason to recreate the circumstances of the original's mystery. Like the Marx Brothers films, there is strictly speaking no need to limit these characters to a certain genre. I would follow Nick and Nora anywhere. They owe me nothing.

Wednesday, March 5, 2008

The 39 Steps (1935)

It so happens that this is the earliest Hitchcock movie I've seen--Juno and the Paycock, the Manxman, and The Mountain Eagle; they may be masterpieces all, but they will probably remain unseen by me. Early though it is, watching it I am completely convinced by the Auteur Theory. Nearly every scene bears the Hitchcock stamp: blondes, trains, the Macguffin, a meet-cute (R. Ebert), the strange genre of the spy-thriller/comedy, the open secret protected by the (in)attention of a crowd, etc.

Hitchcock occupies a strange place in the canon of "old films that most people have seen and liked"-- remarkable because of how many of his films are regarded as classics by an undiscerning public (eight or so), how entirely suitable for every taste they seem to be, and how continually ahead-of-their-time they seem to be. That all sounds very banal, but I dare anyone to think of another director so... so very popular! with everyone! The only possible rival is of course Howard Hawks, but Bringing Up Baby, The Big Sleep, Rio Bravo, To Have and Have Not, and Sergeant York don't hang together at all in the same way as Hitch's ouevre.

The 39 Steps is a great Hitchcock film. I prefer it to Spellbound, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Birds, and Rope (to name only the duds among his famous movies). The pacing is flawless, the leads are likable, and there are five or six indelible shots (in a movie that is extremely "light" and not at all striving for indelibility). Mr. Strick and I will often mention Howard Hawks' definition of a good movie as "three great scenes and no bad ones"-- The 39 Steps has a dozen great scenes, easy.

On the back of my copy of Tolkien's Fellowship of the Ring, there is a blurb by W.H. Auden comparing it to The 39 Steps, the novel by John Buchan, "on the primitive level of wanting to know what happens next," in which I suppose these works are supreme. But Hitchcock's vision is immeasurably more profound than the good-evil world of Middle Earth: the world of this film is populated with indifferent, newspaper reading persons, who find it hard to believe anything outside of their routine gossip, who can barely be bothered to interfere in a matter of the greatest national importance. In short, a world of idiots. All of the intrigue which fascinates us, barely arouses any attention from the bumbling background of human life, which at most aspires to a local nosiness.

Perhaps one doesn't think this while watching the film, but what occurs to me while reflecting upon it is, "how unfortunate that the character cannot go back through every location, after it's all over and done with, and find everyone whom he had to evade or deceive, and let them know that they had been wrong and/or simply in the way!"

Monday, March 3, 2008

Vampyr (1932)

Many who have seen Vampyr will remember--misremember--it as a silent movie. There is spoken dialogue, to be sure, but very little, nearly all of it inconsequential, and much of the film's brief running is taken up with still shots of a book about vampires. It would be very easy to guess that the film was a hold-over from a silent project, and that very little was done to bring it up to the expectations of a talking picture.

As we have been taught to do with early horror films, the proper thing indeed is to gush over the "atmosphere" presented here. Much of this atmosphere is unintentionally masterful and weird, such as the entire thing (a vampire film, I remind you) being shot in broad daylight. The first scenes are precisely Kafkaesque: sparse, claustrophobic, shadowy, and peopled with halting and confused villagers. The latter half of the film is incoherent, and no one will find the "horror" suspenseful--the titular vampire is a slow-moving old woman. The saving point of the second half is a long "burial alive" dream sequence that is suffocatingly slow (and, from a modern point of view, refreshingly unexplained).

What can we learn from this film? For one, even this too-late development of the silent film was remarkably anti-theatrical. There is hardly 40 seconds of this film that could be staged. Compare this with the Hollywood Dracula (Tod Browning) of the previous year, which began as a Broadway play. [Sidenote: evidently the technically superior version of this Dracula is the spanish-language version simultaneously produced by Universal Studios, which has, from what I've seen, far more dramatic and engaging camera work.] Vampyr: only 70 minutes long, anti-climactic, confusing, and reliant on long stretches of explanatory intertitles, barely knows what it is to be a MOVING picture, much less a talking one. But its ambition is less to be a filmed record of Aristotelian drama than to be *illustrative*. A few indelible, recurrent still images dominate the film: the man with the scythe (above), the hero's face under glass, a distorted feminine grimace, and an angel's silhouette.

While I cannot recommend Vampyr, with its narrative incompetence and long boring stretches, as entertainment, nor--for Dreyer was certainly on the "wrong side of history"--for its influence, the film asks an important question: why is it that we do not ask our horror films to any longer resemble, exactly and uncannily resemble, our bad dreams?

Wednesday, February 27, 2008

Oscar predictions revisited

Enough about me. For the second year in a row, the best picture of the year won best picture of the year. This has not always been the case. Let's just do it. Here's a list of great films that really, truly lost big. So, I didn't include Citizen Kane, which lost to How Green Was My Valley. A good film, even if it's no Citizen Kane. This is not even including great films that were never nominated, like Strangers on a Train, Miller's Crossing, Rosemary's Baby, or Mean Streets. Winner in parentheses.

Dodsworth (The Great Ziegfield)

Double Indemnity (Going My Way)

High Noon, The Quiet Man (The Greatest Show on Earth)

Romeo and Juliet (Oliver!)

Taxi Driver (Rocky)

Apocalypse Now (Kramer vs. Kramer)

Raging Bull (Ordinary People)

The Right Stuff (Terms of Endearment)

Goodfellas (Dances with Wolves)

Pulp Fiction (Forrest Gump)

In the Bedroom (A Beautiful Mind)

The strongest year for this category is either 1941: Seargent York, How Green Was My Valley, Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, and Suspicion---or 1975: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Barry Lyndon, Dog Day Afternoon, Nashville, and Jaws.

Also strong is 1953 (From Here to Eternity, Julius Caesar, Shane), 1961 (West Side Story, the Hustler, The Guns of Navarone), 1967 (as discussed in this NY Times article), 1973 (Cries and Whispers, American Graffiti, The Exorcist, The...uh... Sting), 1981 (Raiders of the Lost Ark, Reds, Chariots of Fire).

Some years are total crap: maybe Rain Man *was* the best movie of 1988! American Beauty was horrible, but would I have preferred The Green Mile?

In conclusion: the Oscars show was boring and endless, but it was a good year for movies and the major awards are not likely to be looked back upon as mistakes twenty years from now.

Saturday, January 26, 2008

Cloverfield

Cloverfield is a movie with many, many problems—and although I saw it only a few hours ago, it is not aging well.

The premise of the movie is simple: Godzilla meets Youtube. This premise is also stupid, as a few seconds of thought will show: a special-effects picture sits uncomfortably within a very up-close portrayal of a group of friends. Take away the gimmick (everything on screen is "found" footage taken on video camera), and one is left with the not-so-bad idea of a monster movie which focuses more on personal tension and group dynamics than the monster. There are films like this, no? I'm thinking of Night of the Living Dead especially, but experts in the genre will doubtless name more.

The most obvious precursor of this film is The Blair Witch Project, which I admit I rather like, but which is, in the most important way, nothing like this film. Blair Witch is not a special effects movie in the least. Cloverfield balances a Bruckheimer scenario with a structure inimical to that scenario. Granted, that is the "angle" here—but it doesn't work. The counterintuitive remains so.

The best shots in the film are the glimpses of the monster down long avenues, partially blocked by buildings, and of destruction that cannot be made out very clearly. Basically: the film does chaos very well. This is to be expected, as even a wedding video made on handheld camera can be very disorienting and chaotic. But—and here's the catch—the handheld camera totally fails to make interesting the kind of personal interactions that become obligatory within that format.

For what it's worth, I also did not like the monster. And the film's knowledge of New York City was annoyingly wrong.

Now, the first thirty minutes of this film, derided by Manohla Dargis in her uncomprehending, pretentious review, happen to be the best in the movie. At times, I wish I had written it. The initial scene-setting—here's what genius—fails to set up anything of interest. The characters are vacant, their problems are petty, they lack all insight, etc. Ms. Dargis sees this as somehow a mistake, an accident. If we are supposed to care about these characters, then, yes, it's a mistake—and there are signs of "feelings" that crop up later in the movie that suggest, yes, this film has made a serious misjudgment of my investment in it. Nonetheless, the bland, at times pitch-perfect inanity of yuppie dialogue is (although a bit theatrical) among the better writing in recent films. It's a party I'm glad to leave, and a group of people I don't mind seeing killed (although the women are unbelievably beautiful and also a bit of a liability for the film's realism)—but as a 30-minute short film about idiots and their lives, Cloverfield's opening scenes are a kind of accidental genius.

Unlike I am Legend, Cloverfield never made me feel like New York City was the very scary place that in reality it is. Nor did I feel, as with The Birds or Dawn of the Dead, as though the monster(s) not being there would have still left an interesting drama (maternal issues and suburban capitalist brain death, respectively). If in I am Legend, I felt sometimes, "I wouldn't go into that doorway even if there weren't zombies there!", Cloverfield failed even to make a swarm of subway rats frightening, which I wouldn't have thought possible.

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Oscars-- Thoughts

Sunday, January 20, 2008

No Country For Old Men

Because I try to see every movie the week it comes out, these were my questions when I went to see No Country for Old Men a second time. (My first viewing of the movie predates this blog--has it been so long?) Surprisingly, the show was nearly sold-out, and my cavalier attitude ("The theater will be empty!") resulted in some crappy seats. Anyways, enough about that, but I am as surprised as you are that some people wait more than a month to see the best-reviewed movie of the year. And in New York! Well, as Derek pointed out, maybe they were all re-watching it, too. Let's pretend that's true. Enough throat-clearing.

*

No Country for Old Men:

*is a period piece

*does not make me want to read the novel it is based on

*has no score/soundtrack

*contains gut-turning violence

*improves on second viewing

*is simultaneously an action film (a la The Terminator) and a genuinely philosophical thought-piece

All of that deserves a lot of print, especially the first two bullets, but the only interesting question for me right now is, is this a better film than There Will Be Blood? For many viewers, this will come down to the endings. No Country ends with Tommy Lee Jones, who is underutilized through most of the film, relating a very poignant dream about his father. It is an abrupt ending, though I'm not sure why, because it is such a classic "modernist" ending. There Will Be Blood's ending alienated many viewers, because it neither concludes the story happily, nor gives a precis of its "meaning," nor shows character growth, and is petty, brutal, and tonally abstruse.

One has to ask, how would we feel about Oedipus' freak-out at the end of Oedipus Rex, on a movie screen today? Or, worse--Oedipus at Colonus? If we don't think about "story," and focus on...affect? irony? catharsis-- There Will Be Blood ends much better than it first seems. Compare the final shot of the Godfather, Part 2: the flashback to the complete family around the dinner table---that is not "part of the story," you see? Not that the film succeeds at the high level of those masterpieces, but I think this is the logic.

No Country For Old Men, however, is philosophically more troubling, and its refusal to take itself as seriously as There Will Be Blood lets the dialogue breathe more--it is less didactic. If the monster in There Will Be Blood dooms himself, there is no satisfaction in No Country that we are walking out of the theater into a safer world than that onscreen. As a defunct blog remarks, "this is the real virtuoso shit." That could be said for both films, but No Country for Old Men is positively Shakespearean, while There Will Be Blood is ultimately only Faulknerish. If PT Anderson wants us to "unblinkingly" observe this nightmare life, the Coen brothers have put more thought into their "world." And, I think it bears saying, our world.

Friday, January 18, 2008

Addendum to "Berlin Alexanderplatz" exhibition-review

Monday, January 14, 2008

Persepolis

Many will wonder why an animated feature, already dubbed into French, could not have been recorded by English or American actors for our shores. The only justifications are 1) money-saving, 2) the prestige of a "foreign film," and 3) artistic necessity. Probably it was a mix of all three. Many of the lines are clearly intended to be delivered in French--it is not, that is, the Persian of Marjane Satrapi's childhood which is being translated into French; the *emotions* and tics here are decidedly French. But, most of that is lost in the subtitles. An idiomatic English-dub would have preserved more than is lost. As it is, if you cannot understand some French, you will likely find it a bit Babar-esque.

The animation itself looks fantastic: it is the graphic novel "come to life." One never feels far from the paneled world of the comic, and yet the movements and scenes are gorgeous and not at all "sketchy." Most animated films today (and this should still be said) are ruined by computer-animation and "rendering" techniques that miss the whole point. Persepolis at least understands what it is to be a cartoon. This is all the more to its advantage, because the illustration does cute kid, puppet shah, sexy 20-something, riot/massacre, and historical summary all very deftly, in different styles but without seeming to be so.

Alas, the movie is too long, and runs out of steam fairly early. As with the graphic novels, part one (her childhood in Iran) is more interesting than part two (an adolescence in Europe and early 20s in Iran). Because it is a memoir, I suppose I can't critique the narrative structure so much, but the pay-off here is very slight. And although adult Marjane has the best scene (an inept, heavily-accented singalong to "Eye of the Tiger" w/ training montage), she mostly loses out to her earlier, cuter incarnation.

In short, I have read three graphic novels in my life, and the other two (Fun Home and Maus) were both better than Persepolis. They probably could not be made into as successful films as Persepolis, because Fun Home treads the same narrative territory over and over, and Maus is split into two stories forty years apart, but overlapping. Persepolis is straightforward and lends itself to this sort of thing (a film version), and if the film captures nearly all the charm of the graphic novels, it also keeps their flawed structure and the drifting of the audience's sympathy and interest.

Sunday, January 13, 2008

Slow week for movies in New York

This week I hit up the Preminger retrospective at Film Forum. The movie I saw, Saint Joan, is held by no one to be among Preminger's best work. It is an ill-conceived adaptation of Bernard Shaw's play, and like many stage-to-screen productions, does not know where to proceed, and is framed awkwardly. I hesitate to make a sweeping judgment on Preminger's ouevre without having seen very many of his films, but aside from Laura, I have not liked what I have seen. More damningly, I think, the casting of Jean Seberg here (in Saint Joan) is a debacle. She cannot deliver the dialogue at all. While Jean Seberg is astonishingly good-looking, her acting is distractingly bad. Apropos another Preminger/Seberg film, Bonjour Tristesse, one is forced to read Truffaut's remark that it is "Preminger's love poem to Seberg," as "he must have been fucking her." Which, whether it is true or not, is basically the only excuse for the shoddy Saint Joan.

And I ponder aloud, is there any justification for our "revisiting" Preminger? As a corollary to the oft-asked "Is nothing sacred?", we might propose an alternate, "Is nothing assuredly and definitively hacky?" Must we constantly revive such second rate bodies of work? Preminger=a director whose talent I am willing to leave as a question settled in the negative.

Is Persepolis the only game in town this week, then?

Thursday, January 3, 2008

There Will Be Blood

As many know, I am a big fan of western movies, and over the past few days I have re-watched Red River and Destry Rides Again, both fine classic westerns. There was a recent New York Times Magazine article about the return of the Western to Hollywood, by which was meant 3:10 to Yuma, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, There Will be Blood, and No Country for Old Men. I don't know if that is a meaningful trend: even if one includes The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, Brokeback Mountain,The Proposition, and Open Range, well...well, then that actually does start to look like something.

Among the films just listed, several are in the Sam Peckinpah/spaghetti western vein of extreme violence: The Proposition may be the most violent film I've ever seen, and even the middle-agey Open Range and the art-house Jesse James were notably brutal. And, albeit in a different way, No Country for Old Men is not a film I would let my mother see even five minutes of, it's so violent.

If I was like John Ruskin, tallying up the number of deaths in Dickens' Bleak House, There Will Be Blood would have a relatively low "body count." But the movie is violent not in the sense of being-rated-R-for, but in the sense of a violent jolt, a violence-against-nature--in the sense of being physically intimidated for 2 hours. Violence is done to the viewer; you get up a bit shaken.

Many people have remarked and will continue to remark on Daniel Day Lewis' performance in this film. Deservedly so. His posture alone, in the scene where he meets his brother, deserves an Oscar. So does the score--No Country for Old Men brilliantly dispensed with any score; the intense and eerie score here seems the only possible convincing response. Like No Country for Old Men, the editing is superb and not at all new-fangled. And if Daniel Day Lewis is channelling John Huston (in Chinatown) here, PT Anderson is mining the Kubrick of Full Metal Jacket and Barry Lyndon here: epic discomfort.

I can't give a "reading" of the film without giving a great deal away, so I will stop at saying that, with some faults--mostly of excess--this is a unique accomplishment and completely blows away both the glossy Best-Picture-winning and navel-gazing indie films that have dominated American cinema since...let's tentatively say since The Silence of the Lambs or the previous Coen Brothers triumphs, Miller's Crossing and Barton Fink. I may be getting carried away, but everything certainly looks weak and vain next to this movie. Especially bad in comparison is The Gangs of New York, or a film like Training Day. Here really is a film with superb editing, great dialogue, virtuoso acting, a perfect score, and a vice-grip on its story line. These differences between this film and the usual critically-lauded prestige picture lead one to honestly ponder when and why we came to expect anything else.

Wednesday, January 2, 2008

The Orphanage

Which, technically speaking (and this comes out like 5 minutes in), the woman here (Belen Rueda) is not. Her (ridiculously adorable) child is adopted, but that seems to have no bearing on anything else in the movie. Is there some trope I'm unaware of, where orphaned children can't have children of their own? So, that doesn't signify anything. And neither do many other aspects: there is a great boring swath running through the middle of the film, until the movie abruptly snaps back into the concerns of its early scenes.

Many people will think that a film all taking place in one location, Aristotle-style, will add to its intensity: The Innocents, The Haunting, Die Hard, etc. This is not true for The Orphanage. I got bored with the location fairly early on.

The first hour of this movie is pretty solid, but only because it handles things in a manner alternately relaxed and contemporary, then "classic," then Hitchcockian (one scene only: see spoilers), only occasionally sliding into a "nowadays horror" vibe. Everyone seems to want this film to be the anti-Saw, the anti-Hostel, the anti-Rob Zombie. But that seems to me to be apples/oranges. What ought to be remarked upon is how very *2007* the film is: the editing, the title screen, the numerous production companies involved, the boring music, the CGI, the casting, the reliance on spooky children still lingering from recent Japanese horror exports, etc. It is definitely a post-Amelie movie, and no one will be confusing it with The Haunting or The Innocents.

****SPOILERS****

Obviously the filmmakers thought they had a good Freudian scare going here. The central mystery, the search for the HIV-positive (this also signifies nothing for the film) child turns around another mystery-axis, namely the return of something unwanted and unsearched-for: the parallel death of a deformed child years earlier. To spell it out, the deformed child was "hidden away" in the past, and so it's return is specifically the return, not just of any ol' dead kid, but of something that had better remained hidden. But the movie drops the ball here, as after a tasteless (read: wonderful) scene in which the frantic mother begins to tear the (inexplicably-provided) masks off of a number of retarded children on her lawn, searching for her son, but then never builds on that real breach of propriety and only gestures wholesomely towards the theme (of disturbing and creepy special needs kids) afterwards.

The Hitchcock moment is the recognition of the "social worker" in a different town altogether, on the street, just before the best shot in the film. It is truly unexpected and yet (for a split second) not at all "scary"--the street is well-lit, the woman is going about her business in a way we figure she has been for months, and she seems *not to recognize* "us" either.

About the ending: The Others, Dark Water, and this film all end the same way. The mother is "united" with her children in an afterlife of maternal bliss. The "real world" is escaped so that the fantasy can be carried on endlessly, spectrally. I do not see the cinematic or signifying appeal here; that could just be me.